Pande, Schaner & Troyer Moore in The Indian Express: April wasn’t January

Neither pollution nor congestion significantly decreased as they did during the January experiment. An enduring solution lies in scaling up the smaller, successful programmes.

This article first appeared in The Indian Express on May 13, 2016.

Delhi has now had two encounters with the odd-even pilot experiment. The first, in January, succeeded in reducing pollution by about 10-13 per cent, as we showed in a previous article (‘Yes, Delhi, it worked’, The Indian Express, January 19). But this time around, we find no evidence that the same policy, running from April 15 to April 30, affected pollution levels. This difference illustrates an important point we have made before: That the odd-even policy is inherently unpredictable and ultimately is likely to have an insignificant impact on pollution. In the long run, other approaches are likely to be better suited to reduce pollution. The difference also underlines why context matters. Different conditions require different measures, and government action in one arena can undermine efforts in another.

Before going further, it’s important to understand the methods we used to arrive at these estimates. We deployed what is known as a difference-in-differences approach. This involves comparing changes in pollution trends in an area where a policy did occur to a similar area where it did not. The point of this approach is to control for external factors that influence pollution outside of the policy. For example, April has seen crop burning and forest fires in Uttarakhand. Certainly, these factors influence air pollution levels and trends in Delhi. But they are likely to equally affect the rest of the NCR too. The method we use therefore can account for such external factors and then examines policy impacts. We used data only from government monitors in Delhi, Faridabad and Gurgaon.

So why didn’t the April pilot work when the January program did?

One reason might be the differences in atmospheric conditions between summer and winter. In the winter, air pollution stays trapped close to the ground in Delhi (a phenomenon known as thermal inversion). As a result, short-term policies to reduce air pollution such as the odd-even scheme can have a brief, detectable effect. The summer, however, is very different. Pollution rises and quickly disperses. As a result, it is less likely that any short-term policy will have immediate and significant impact on ground-level air pollution.

There are other factors that might be at play that demonstrate how one policy may impact another. During the April odd-even scheme, private taxi services such as Uber and Ola were banned from using surge pricing. When peak hour taxi prices are constrained to be low, then supply may also drop at these times. Indeed, taxi availability through online services was very low in the second half of April and it is plausible that this made it hard for some consumers to find an alternative. In general, constraining prices in the private market is inefficient policymaking. On the flip side, increasing government enforcement of the diesel ban on commercial vehicles, while a good idea in the long run, might have further constrained taxi availability during this period.

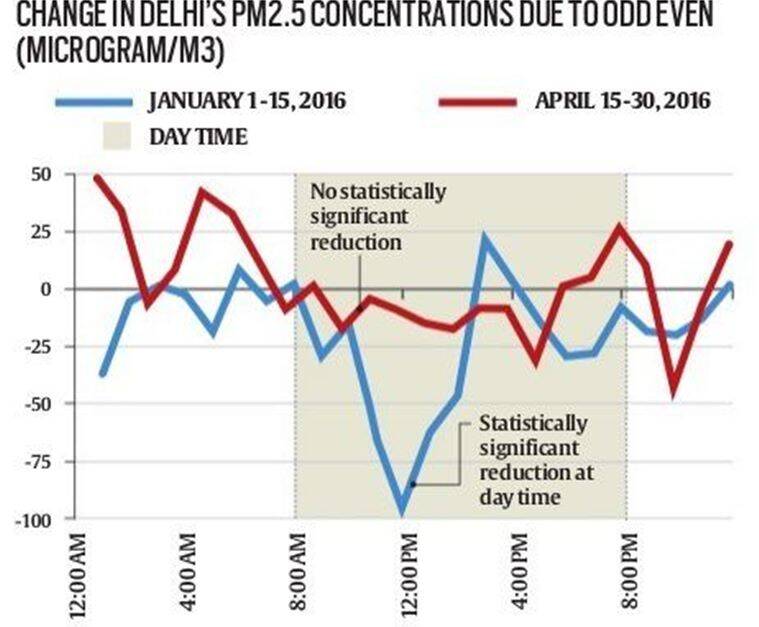

The chart accompanying this article sharply illustrates the difference between odd-even in January versus April. In our previous article, evaluating the January odd-even scheme, we found that pollution reductions started to become visible around 8 am, with the maximum declines appearing between 11 am and 2 pm. As temperatures fell and 8 pm approached, reductions became smaller. Overall, we estimated that pollution levels dropped by an average of 20-30 microgram per cubic meter during the hours when the program was in place.

This time around, things look very different. Hourly estimates of pollution reduction are small. Indeed, none of the hourly estimates for the second round of odd-even can be statistically distinguished from zero. These estimates suggest congestion and vehicle use did not significantly decrease, as they did during the January iteration.

What then might we conclude from this?

One argument has been that the odd-even policy should be extended over a longer period of time. But experience proves otherwise, as humans learn to adapt and game the system. In Mexico City, where an odd-even program was enforced over a longer period of time, pollution reductions vanished as commuters bought cheaper, second-hand and often higher-polluting cars. The only thing these vehicles had going for them was the right number plate. It is very unlikely that this is a factor in India currently. But, if the scheme was extended, Delhi might experience something similar to Mexico City.

Watch video Delhi not the most polluted city

A more successful longer-term measure may be to adopt congestion pricing in areas where local pollution levels are high and traffic jams are common. In such a system, drivers are charged for using the roads at certain places and times, allowing cities to effectively reduce car use at periods of peak congestion and pollution. This approach has been successful in places such as London and Singapore. Alternatively, taxing actual fuel consumption might also be a sustainable long-term policy if designed well.

With programs such as these that use financial incentives to change behavior, it also becomes possible to raise revenue. Any revenue could then be used to improve the quality and capacity of public transport. In the long run, this is the most effective way to reduce the use of cars and traffic congestion, while also directly impacting air pollution.

With Delhi’s air pollution being such a critical challenge, it is important that the best policies rise to the forefront. That means all of the schemes the government implements should receive the same level of public scrutiny and testing. But programs like the environment compensation cess or the vacuum cleaning of city streets have not received much attention or evaluation. Delhi’s air urgently needs all of these programs to be implemented and tested with as much political will and public involvement as the odd-even program.

That has been the one unqualified success of the odd-even program: It has placed the issue of Delhi’s air pollution front-and-center in public discourse. This public visibility needs to be built on by piloting, testing, and scaling up the successful policies.