Pande and coauthors: Empowering women through direct digital payments

New research by Rohini Pande of EGC, Charity Troyer Moore of the MacMillan Center, and coauthors shows that giving women in India’s Madhya Pradesh state greater digital control over their wages led to a surprising range of benefits.

Inclusion Economics Research Summary, June 2021

A large-scale policy experiment sheds light on the role gender norms play in India’s low and declining rate of women in the workforce – and how to bring more women into the labor force while altering such norms.

The relatively simple intervention – providing poor women in rural Madhya Pradesh state with direct deposit of wages from a government workfare program into their own bank accounts, along with a basic account orientation – led women to work more outside the home, and liberalized their beliefs about women’s ability to work. The study shows that policies that boost women's financial control can expand women’s autonomy.

India is an outlier among nations at a similar level of development with its low rate of women in the workforce – an impediment to economic growth, not to mention women’s autonomy.

Traditional beliefs about gender roles limit women from working – but it is unclear how such norms function or how they can be changed.

A policy that increased women’s control of their own wages in the government’s workfare program led them to work more, both in workfare and – surprisingly – private employment. Compared to women who just received bank accounts, those who additionally received bank accounts, direct deposit, and training in account use earned 24% more in private-sector employment annually.

Women in this treatment arm were more likely to have a positive view of women and work. They reported in surveys that a working woman made a better wife and the working woman’s husband a better husband and provider.

Their perceptions of the views of other people in their community also changed: the women were less likely to say women bore social costs if they worked outside the home.

Read the publication

Erica Field, Rohini Pande, Natalia Rigol, Simone Schaner, and Charity Troyer Moore. 2021. “On Her Own Account: How Strengthening Women’s Financial Control Impacts Labor Supply and Gender Norms.” American Economic Review 111(7): 1–34.

Economists have observed that women’s participation in the labor force follows a U-shaped curve as a country develops. This is typically understood as reflecting multiple trends: In poor countries, a high number of women work, particularly in agriculture; then, as incomes rise women exit the workforce to focus on caregiving and maintaining the home. Later, as a country enters middle-income status, women tend to have fewer children, attain more education, and they move back into the workforce as they can earn more by working.

The case of India, however, shows that other forces can keep women from joining the labor force. Between 2005 and 2018, a period of strong economic growth, India rose into lower middle income status. Fertility declined and women’s educational attainment increased – yet female labor force participation declined from 32 to 21 percent. And despite this low level of female labor force participation, in a national survey, one third of Indian housewives report interest in working outside the home.

What is keeping India’s women from working more? Gender norms are a clear and potentially important barrier to women’s economic activity in India. In conservative areas, the husband is often expected to be the primary breadwinner, and a wife who works for pay is seen as a source of social stigma or shame. This is consistent with national survey data, where a majority of Indian women report their husband has the greatest say in whether they can work outside the home.

Read more about women & work in India

India's falling rate of women in the workforce represents a puzzle for researchers and a challenge for policymakers.

In settings where women stay out of the labor force because of restrictive gender norms, could giving women greater control of their potential wages induce them to work, and empower women more broadly? And could this increased financial control liberalize restrictive norms around female work? The research team set out to answer these questions.

Ishan Tankha

Ishan Tankha

Findings

Working in northern Madhya Pradesh, a setting with strong gender norms, the research team collaborated with government partners to enable direct deposit of women’s wages from the federal workfare program into their own bank accounts rather than into a male-controlled household account. The study covered 197 village clusters (gram panchayats) and surveyed a total of 4,300 women.

In one treatment group, women received an account, direct deposit of wages, and a short training on how to use the local bank kiosks that serviced these accounts. These women are termed financially empowered in the findings below.

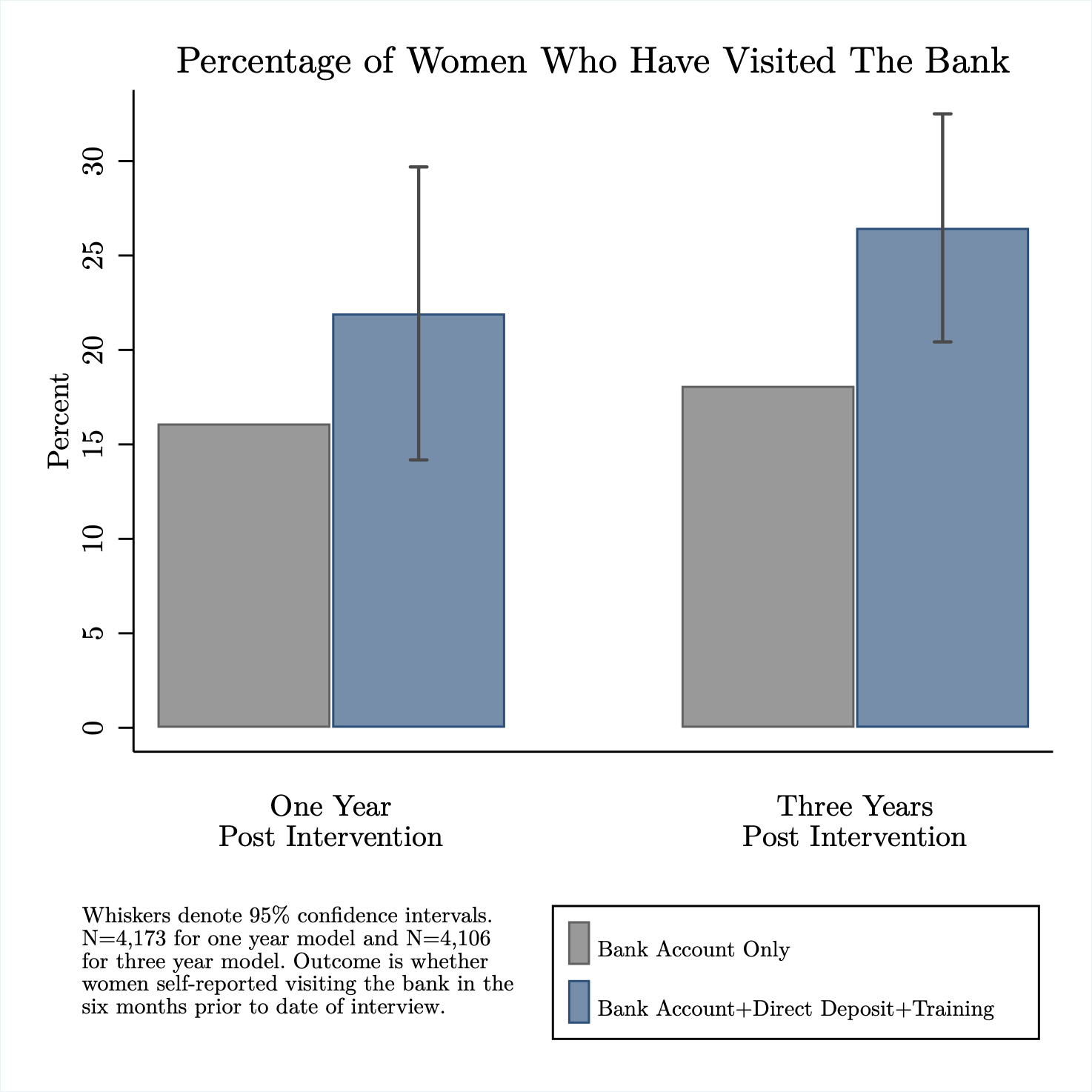

Financially empowered women became more engaged with banking.

Figure 1 shows this increase in engagement with banking persisted at follow-up surveys 1 and 3 years after the intervention. There were similar trends for reports of being an individual account holder.

Figure 1

Financially empowered women worked more.

The study found an overall increase in labor supply among financially empowered women compared to women who only received a bank account.

-

They were 8 percentage points more likely to work in workfare program in the last year

-

They were 5 percentage points more likely to have reported any paid work in the past month.

- They earned 24% more (950 Rupees) in private-sector earnings annually.

The increase in private-sector employment is notable, as the intervention was linked only to their workfare wages. This suggests that the effects of digital control over wages spread into other areas of women’s lives, allowing them to negotiate with household members for the ability to work more outside the home.

The researchers separated the sample into women who had worked in the government program before, and those who had not. Other survey measures confirmed this latter group to be more constrained in other ways: they reported having less decision-making power, and their husbands were more likely to associate having a working wife with social stigma. These impacts persisted at the 3 year survey follow-up for the socially constrained group. In other words, the intervention had the most important impacts on women facing the greatest barriers to work in the first place.

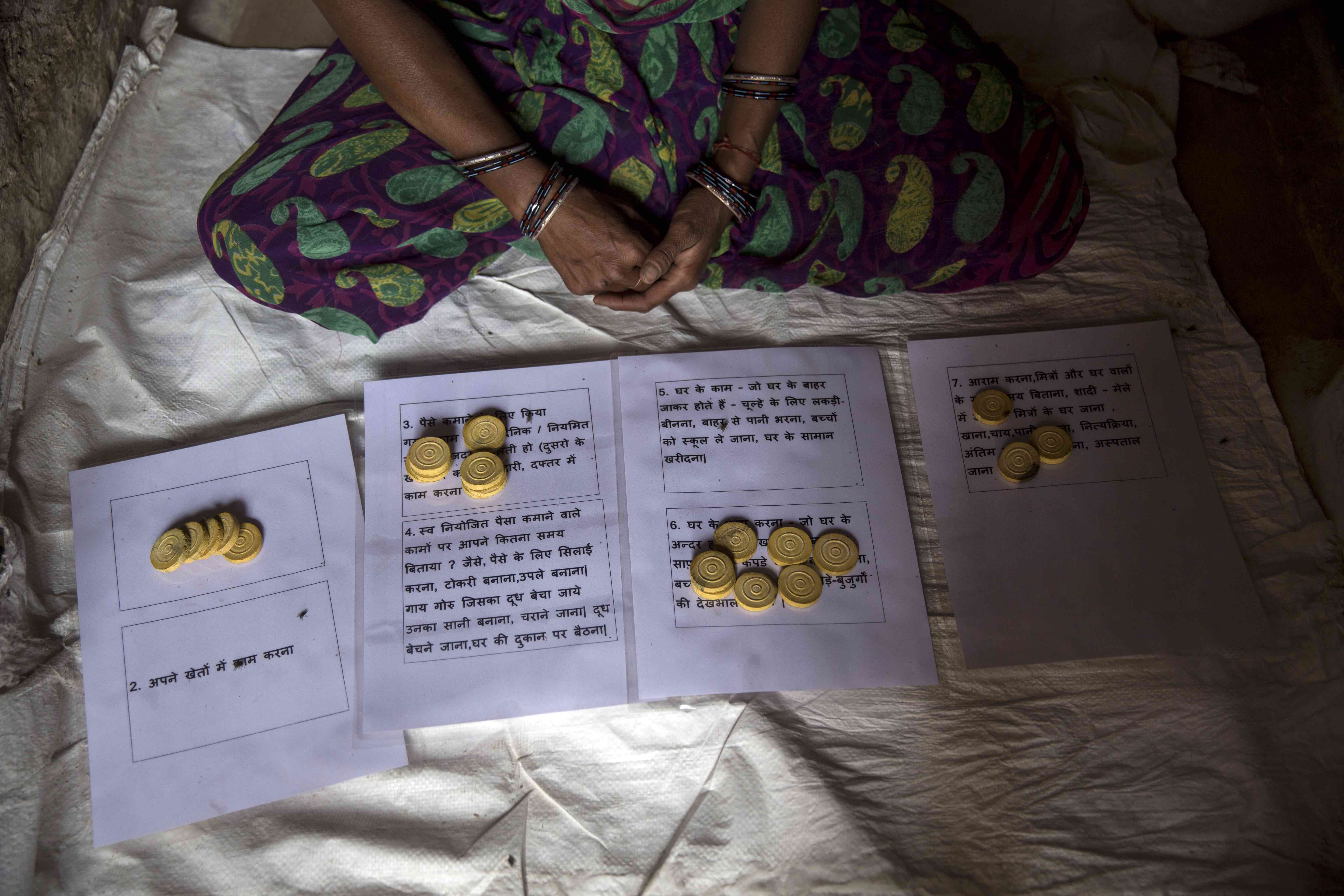

For this study, the researchers developed customized approaches to measure social norms. They asked survey respondents to use game pieces to reflect the proportion of their neighbors who would approve or disapprove of women’s work. Photo by Ishan Tankha.

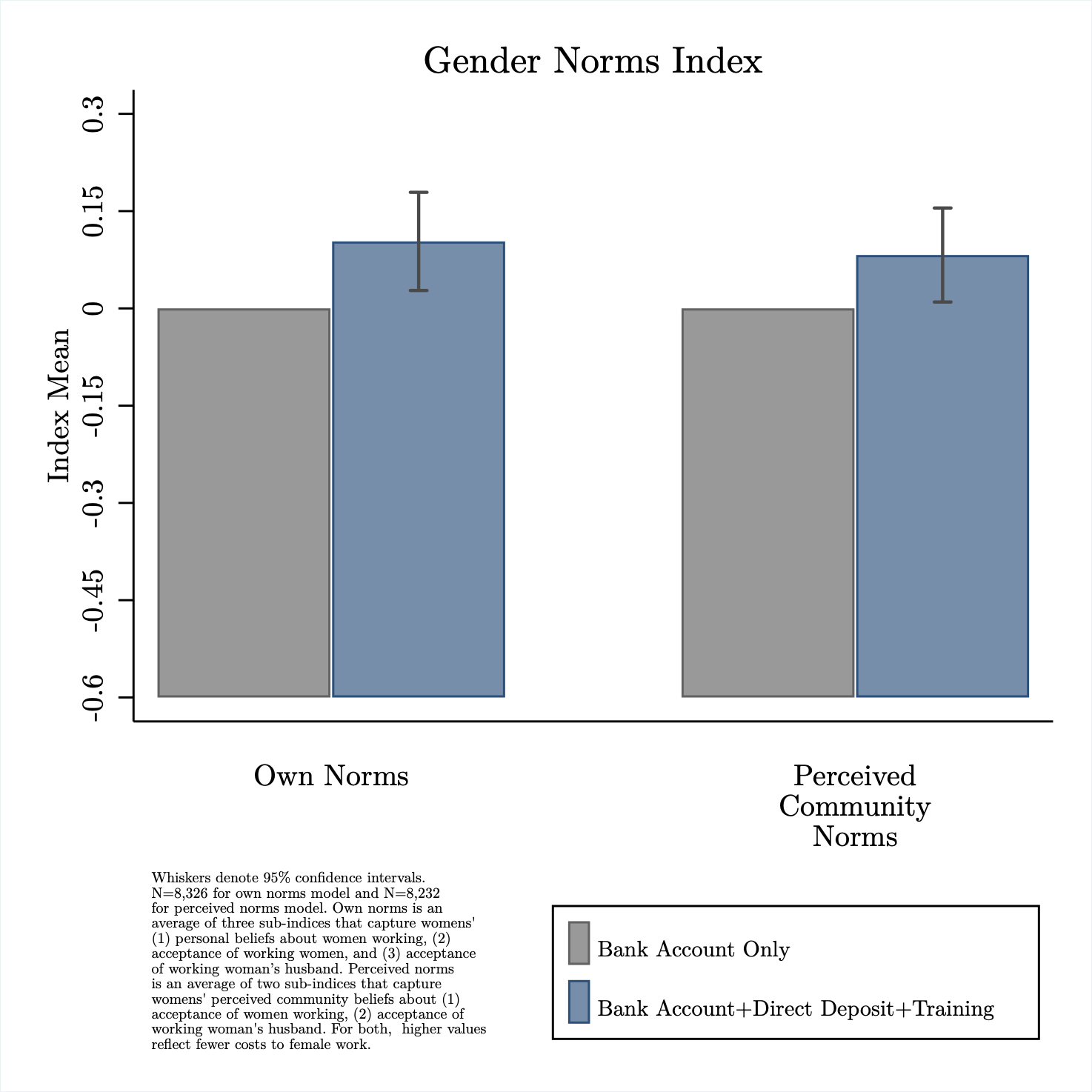

The intervention changed women’s beliefs about women and work.

Surveyors used questions and vignettes to measure how study subjects thought about working and non-working women. The results showed that, compared to women who received only bank accounts, financially empowered women liberalized their personal beliefs about women’s work: they stated more frequently that a working woman made a better wife, and a working woman’s husband a better husband. Other questions confirmed this trend toward more positive views of women’s employment.

Their perceptions of the views of others in their communities also changed: they were less likely to say women bore social costs when they worked outside the home.

Figure 2

The challenge of gender-intentional policy

The Indian government is scaling up direct deposit of workfare wages into female-owned accounts. Designing policy for gender inclusion requires choices and planning. Key elements of this study's most impactful treatment arm included targeted outreach to eligible women and systematic training on how to use accounts. Policymakers seeking to design for gender inclusion might include these activities in further expansions of digital banking.

In the coming years, the growth trajectory of India – still home to the world’s largest population of people living in extreme poverty – will depend on how well it uses public policy to lower barriers to female employment. This study shows how social norms function as barriers, and that folding gender-intention design into social protection programs can get women working and spur social change.

Research Summary by Vestal McIntyre.