Towards Gender Equality Newsletter Issue #6: Gender and Structural Transformation

Our understanding of what is macro-critical has evolved significantly since economists began modeling economic growth and its determinants. We now understand how a virus can grind an economy to a halt, how violence destroys meaningful interaction and exchange, and how leaving sections of a population outside of human capital investment and opportunity as a result of social hierarchies can cost economies in the long run.

We are examining the contours of how economies transform production and reallocate labor and talent across sectors with lenses informed by the past decades of intra-household, institutional, and political economy research. I hope some of these insights below encourage policy and practice to respond with innovative action.

Aishwarya Lakshmi Ratan

EGC Deputy Director

Research Highlight

From Rural Fields to Urban Kitchens: Structural Change and the Decline of Women’s Work in India

Peters, Torola, Uniat & Zilibotti [Working Paper]

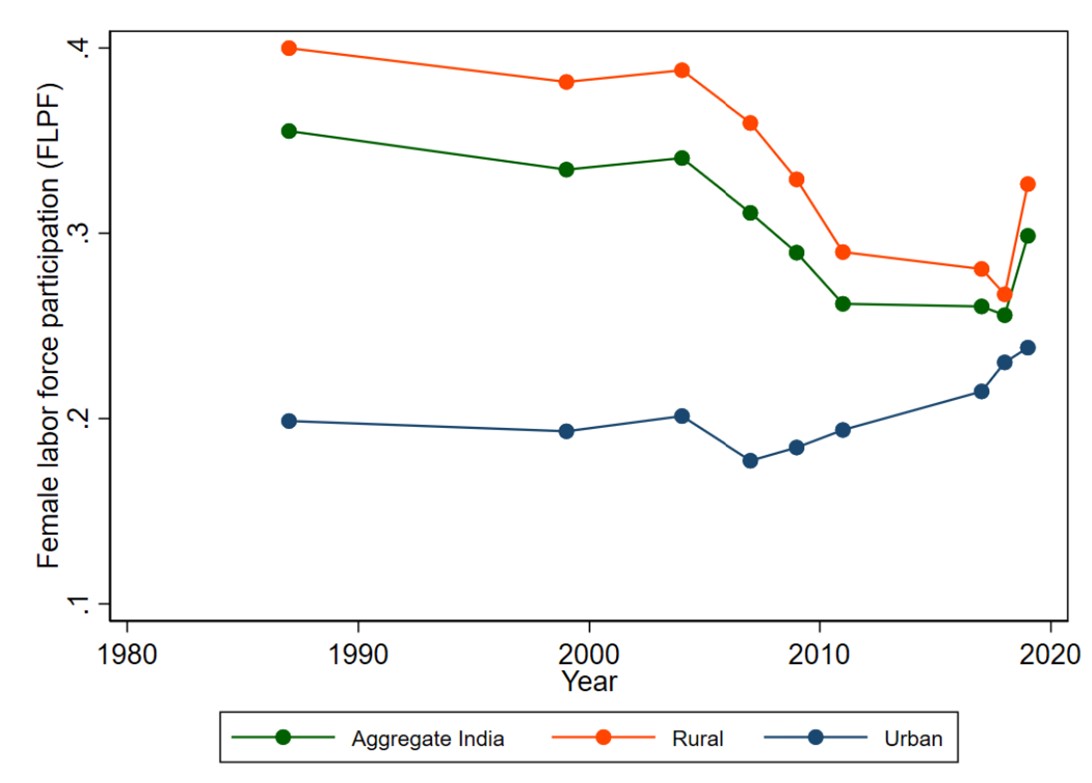

Whilst India has grown and modernized in the past three decades, female labor force participation (FLFP) fell from 36% in 1987 to a dismal 27% in 2019. Moreover, there is a significant rural-urban participation gap, with FLFP lower in better-off urban areas, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Female Labor Force Participation and Urbanization, 1987-2019

Notes: Data Source: National Sample Surveys & Periodic Labor Force Survey, India. The sudden increase in rural FLFP after 2018 is unexpected and may be related to changes in the PLFS sampling frame.

To further explore the relationship between growth, structural change, and FLFP, Peters et al. analyze time use data to uncover patterns underlying the urban-rural FLFP gap. The authors then propose and estimate a simple neoclassical model of household labor supply that effectively captures the trends observed in time use data. Using this model, they run counterfactual simulations to predict how FLFP is likely to change as India’s economy urbanizes and grows over time. The following insights emerge from their paper.

Insight 1: India’s urban-rural FLFP gap arises from urban women doing less part-time and informal work than rural women, opting instead for home production or formal jobs

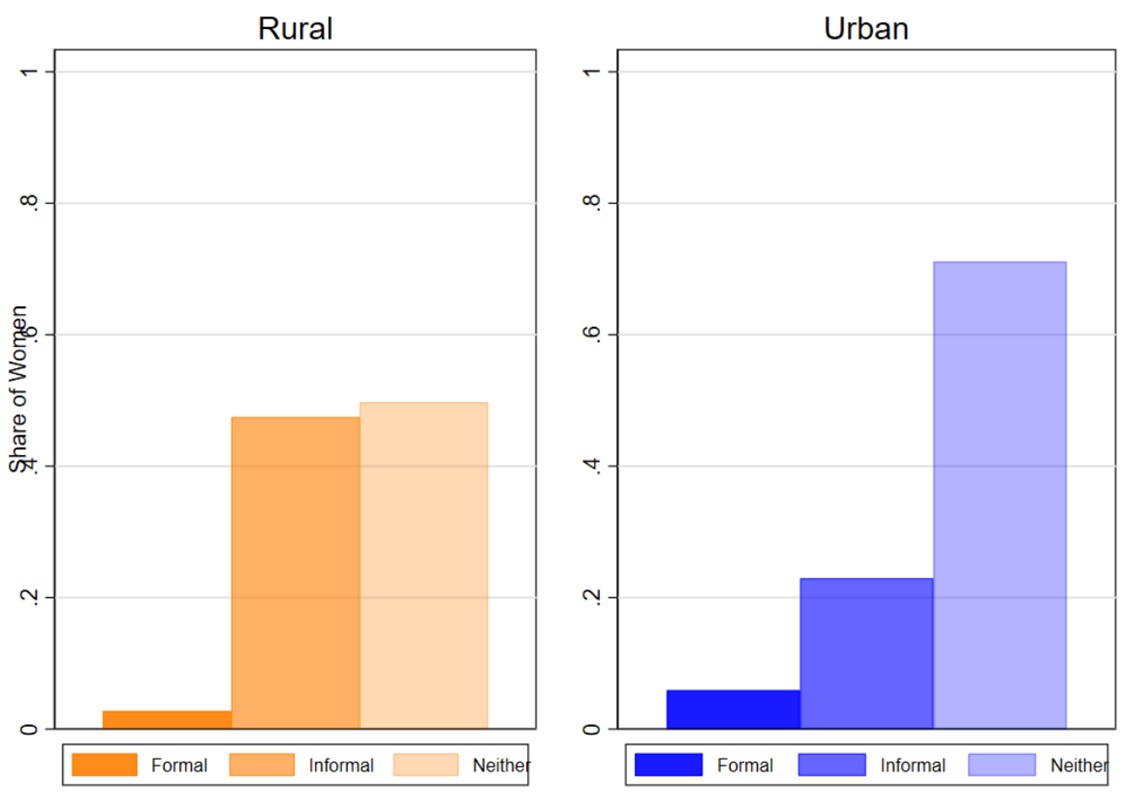

The authors’ analysis of time use data reveals striking differences in the types of labor available to women in rural and urban areas. As Figure 2 illustrates, in rural settings, women tend to engage in low-hour, unpaid, informal work much more than in cities. In contrast, urban women tend to either enter the formal labor market or, more frequently, withdraw entirely from the labor force, focusing on home production and leisure instead. Part of the explanation is an income effect: in urban areas, husbands’ earnings are higher, making households less reliant on a second income source.

Figure 2: The nature of women’s work in India

Insight 2: The urban-rural FLFP gap is driven by differences in productivity, social norms, and labor market discrimination

To rationalize the different patterns of labor supply shown in Figure 2, the authors estimate a neoclassical model of household labor supply, where rural and urban labor markets differ in three dimensions. First, cities might have higher productivity. Second, there might be differences in social norms that limit labor market access for women. Third, labor market discrimination, whereby women are paid below their marginal product, could differ between urban and rural locations. The authors find that demand-side labor market discrimination against women in urban areas is the most salient explanation for the contrast between FLFP in rural and urban labor markets. Higher husbands’ earnings due to high productivity also reduce FLFP by decreasing reliance on a second income as noted.

Insight 3: Economic growth isn’t enough: As Indian wages grow, FLFP will likely decline further in the short run. While the trend will reverse at some point, future gains in FLFP will be modest and accrue slowly.

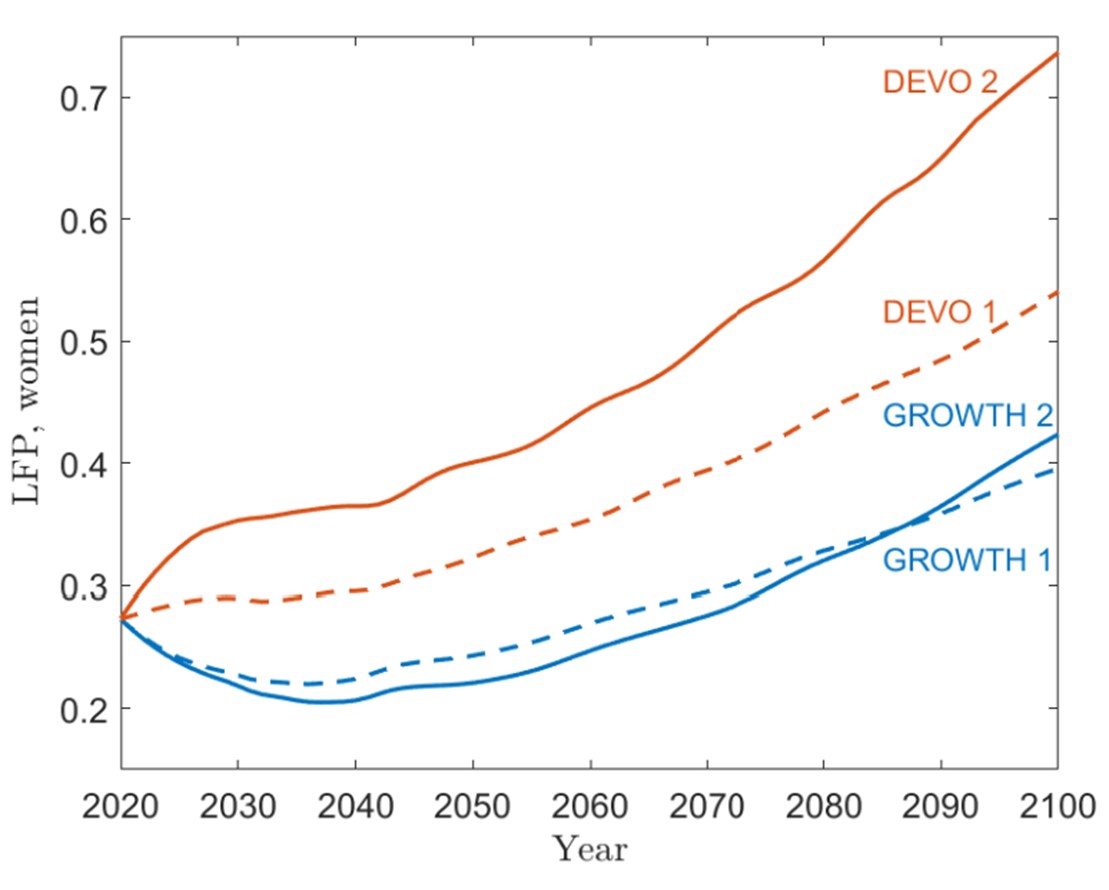

To forecast the future of FLFP in India, the authors then consider various scenarios. Given the importance of both economic and social factors, the authors distinguish between economic growth (i.e. rising productivity and better access to formal jobs) and economic development (i.e. economic growth, falling discrimination, and changes in social norms). The authors' model forecasts a U-shaped pattern for FLFP in India as the wage in formal labor markets grow. Their estimates place India on the downward-sloping side of this U curve, implying that near-term economic growth will likely reduce female participation, as illustrated by the blue lines in Figure 3. The prediction is that over time, rising wages and improved access to formal jobs will reverse this trend as the income effect of rising urban wages becomes outweighed by the substitution effect of the opportunity cost of home production. However, Figure 3 suggests that even after crossing to the upward side of the "U," the growth effect on FLFP will be limited (GROWTH1 and GROWTH2 scenarios).

Figure 3: Model estimates of the evolution of FLFP under four scenarios

Notes: Blue lines titled “GROWTH 1” and “GROWTH 2” are plausible growth scenarios for India, without changes in the level of labor market discrimination. The red line titled “DEVO 1” illustrates the LFP trend if a parameter for labor market discrimination declines, and “DEVO 2” is where additionally, a parameter related to norms against women’s work declines to zero.

Insight 4: To boost FLFP, changes in gendered institutional norms and reductions in labor market discrimination are needed

Meaningful increases to FLFP will therefore not only require economic growth but broad-based economic development - that is, changes in institutional gender norms and falling labor market discrimination. The red lines in Figure 3 above illustrate that if labor market discrimination gradually declines to zero (DEVO1) and additionally social norms against women’s work decline to zero (DEVO2), FLFP will increase significantly from its current level. In both cases, Indian FLFP is predicted to grow significantly with economic development.

Featured Researcher: Tatjana Kleineberg

Tatjana Kleineberg is an economist in the Macroeconomics and Growth team of the World Bank’s Research Department. She holds a PhD in Economics from Yale (2019), and her research lies at the intersection of macroeconomics, spatial economics, and economic development.

Tatjana Kleineberg

Kleineberg’s research studies how labor market frictions affect countries' structural transformation and their regional and aggregate output. In a working paper featured in the “New Research” section below, titled "Gender Barriers, Structural Transformation, and Economic Development," Kleineberg and co-author Chiplunkar examine how employment transitions differ by gender across 90 countries as they undergo structural transformation, and how declining gender barriers have affected female labor force participation, structural transformation, and economic growth in six major economies. In another project, Kleineberg and co-authors examine the relationship between the caste system, occupational choices, and aggregate output in India. Other work by Kleineberg and co-authors investigates the drivers of regional inequality, regional convergence, and migration within countries as well as their consequences for regional and aggregate growth and development.

See Kleineberg’s website for more information.

“Barriers to economic opportunity based on individuals' gender, race, ethnicity, family background, or place of birth create a misallocation of talent and reduce countries' aggregate productivity and growth. Identifying these barriers and evaluating policies to reduce them is therefore an ethical responsibility and a crucial step toward fostering inclusive growth and development.”

- Tatjana Kleineberg

New Research

Gender Barriers, Structural Transformation, and Economic Development

Chiplunkar & Kleineberg [Working Paper]

The representation and significance of women in the labor force has grown substantially over the last five decades in most countries around the globe. Drawing on nationally representative data from over 90 countries, the authors document distinct gender patterns in employment transitions across both sectors and occupations during this time period. Using a model of occupational and sectoral choice and focusing on six major economies, the authors find that declining gender barriers - defined as gender-specific distortions in employment and wages - have been a key driver of the observed rise in female labor force participation, the expansion of the service sector, and increases in real GDP per capita from 1970 to 2018, but with substantial variation across countries.

Gendered Change: 150 Years of Transformation in US Hours

Ngai, Olivetti & Petrongolo [Working Paper]

The contribution of women to the economy has been markedly underestimated in predominantly agricultural societies, due to women's widespread involvement in unpaid agricultural work. Combining data from the US Census and several early sources, the authors create a consistent measure of male and female employment and hours for the US for 1870-2019, including paid work and unpaid work in family farms and non-farm businesses. The resulting measure of hours traces a U-shape for women, with a modest decline up to mid-20th century followed by a sustained increase, and a monotonic decline for men. The authors propose a multi-sector economy with uneven productivity growth, income effects, and consumption complementarity across sectoral outputs. During early development stages, declining agriculture leads to rising services -- both in the market and the home -- and leisure, reducing market work for both genders. In later stages, structural transformation reallocates labor from manufacturing into services, while marketization reallocates labor from home to market services. Given gender comparative advantages, the first channel is more relevant for men, reducing male hours, while the second channel is more relevant for women, increasing female hours. The authors’ quantitative illustration suggests that structural transformation and marketization can account for the overall decline in market hours from 1880-1950, and one quarter of the rise and decline, respectively, in female and male market hours from 1950-2019.

Home Production and Gender Gap in Structural Change

Cao, Chen & Xi [Working Paper]

The authors document that the gender gap in non-agricultural work in developing countries exists primarily among rural married workers, not singles. Rural married women dedicate a much larger portion of time to home production compared to other groups, making them less likely to pursue non-agricultural employment. The authors extend a general equilibrium Roy model to incorporate the joint labor supply decisions of rural married couples, accounting for gender-specific labor distortions and entry barriers to non-agriculture. Calibrating the model to China, the authors find that within-household specialization among married couples greatly amplifies the effects of gender-specific labor distortions, and that changes in entry barriers to non-agriculture widened the gender gap in China between 2000 and 2010. Enhancing public services such as childcare facilities can effectively induce more married women to work in non-agriculture. Extrapolating the model globally explains a quarter of the variation in the gender gap across countries.

Compulsory Education and Gender Inequality in China’s Structural Transformation

Xie, Rozelle & Liu [Working Paper]

Economic growth has typically been accompanied by a process of structural transformation, in which workers reallocate from agriculture to manufacturing and services. This paper examines whether education can play a role in mitigating gender inequality in the process of sectoral reallocation of labor by exploiting the exogenous variations induced by the implementation of the 1986 Compulsory Education Law (CEL) in China. Using data from the 2018 wave of the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) and a cohort difference-in-differences (DID) approach, the authors find that the CEL narrowed the gender gap in education for rural residents, but exacerbated gender inequality in labor market outcomes (e.g., annual wage income, monthly wage, and weekly working hours). The authors’ analysis reveals that this widened gender inequality in labor market outcomes can be explained by gender differences in migration and occupational choices. Specifically, conditional on CEL exposure, rural males tended to migrate outside local provinces and work in low-skilled manufacturing sectors, while rural females were more likely to stay within local counties and work in low-skilled service sectors. The authors further provide evidence that their differential migration responses are related to household labor divisions and social gender norms, but not to gender gaps in cognitive skills.

Structural Transformation, Gender Norms and Intrahousehold Bargaining in Sub-Saharan Africa

Li & Zhang [Working Paper]

The authors find that structural transformation, or service expansion, has widened the gender wage and income gaps in Sub-Saharan Africa. This contradicts the previous findings in developed countries. To reconcile this fact, the authors add a new feature-social stigma against females working in the service sector-into an otherwise standard structural transformation model. The authors show that structural transformation can reduce the female to-male wage ratio and prevent female empowerment if the social stigma exceeds a threshold. The authors test the model using sectoral employment share and individual bargaining data from 15 SSA countries. Using two-way fixed effect and instrumental variable estimations, structural transformation is found to reduce female bargaining power, especially in countries with more restrictive gender norms.

Gender and the Economy Highlighted at Yale

In Conversation: Penny Goldberg & Rohini Pande on Gender & Economic Growth

[EGC Article, November 19, 2024]

In the first installment of EGC’s “In Conversation” series, which pairs Yale economics faculty with various perspectives on international development, Goldberg and Pande, faculty leaders for EGC’s Gender & Growth Gaps project, discuss the complex relationship between gender inequality, labor markets, and economic growth.

Yale Economics Department Magazine feature on EGC and Inclusion Economics’ gender work and Global Gender Distortions Index

[Yale Department of Economics 2024 Annual Magazine]

Yale Department of Economics’ 2024 Annual Magazine features a story on page 9 on EGC’s research investigating the drivers and consequences of gender disparities, including the Gender and Growth Gaps Project and Yale Inclusion Economics’ gender portfolio. Page 17 features EGC’s Global Gender Distortions Index Discussion Paper.

Policy Engagement, Events & Media Coverage

Gender-focused State of India’s Livelihoods Report, including a chapter from Goldberg & Chiplunkar

Access Development Services, an India-based national livelihoods support organization, recently published the “State of India’s Livelihoods Report 2024,” which contains a series of chapters with a focus on gender. EGC’s Penny Goldberg and University of Virginia’s Gaurav Chiplunkar contributed a chapter titled “Female Entrepreneurship and Economic Opportunity for Women” (page 7), which draws on their recent Econometrica paper, "Aggregate Implications of Barriers to Female Entrepreneurship."

Pande speaks at World Bank Prosperity Forum

EGC Director Rohini Pande spoke at the World Bank Prosperity Forum on January 13, 2025, which was attended by 2,000 World Bank staff and focused on "how to create more and better jobs, particularly for women and youth in developing countries." Pande participated in a panel discussion titled "The Future of Work: Global Perspectives on Jobs and Development."

Additional Resources

Why a Gender Lens Matters: Unlocking Solutions to Macroeconomic Challenges

Kolovich, Newiak, Gomes, Gu, Malta & Mondragon [IMF Gender Note]

This IMF paper, part of the "Gender Notes" series, draws attention to how gender lens on macroeconomics can amplify reform impact. It draws on a wide range of evidence to illustrate the macroeconomic challenges that countries face, the gains from gender equality, the extent of progress towards closing gender gaps, and how to put a gender lens on macroeconomic policy.

Intimate Partner Violence and Women’s Economic Empowerment: Evidence from Indian States

Newiak, Sahay & Srivastava [IMF Working Paper]

The authors study the interplay of determinants of a woman’s risk of facing intimate partner violence (IPV) for the case of India—using information from up to 235,000 female survey respondents and exploiting state-level variation in institutions, law enforcement and attitudes. Unless in paid and formal employment, a woman’s economic activity is associated with a higher risk of IPV. However, household and other characteristics, such as higher agency within the household, higher education of the husband, lower social acceptance of IPV, and normalization of reporting incidences of violence counter this association. At the state level, the presence of more female leaders, better reporting infrastructure for victims of IPV, and higher charge-sheeting rates are associated with a lower risk of IPV.